BEFORE YOU READ | In light of recent New York City subway crimes, ranging from stabbings to arson, the nation’s largest public transportation hub is under scrutiny. Cities like Detroit and Chicago are also grappling with challenges related to safety, accessibility and reliability in their transit systems. As a result, many residents and suburban commuters face significant barriers, often preventing them from reaching essential destinations.

Detroit

As she waited at a Detroit Metro bus stop with her aunt as a child, senior Kaylei Butcher-Harris faced a moment of fear that remains vivid even today. An unknown man approached them, claiming he had a gun and bizarrely pretending to be Chris Brown. The incident was not only terrifying to experience but also prompted it to be her first—and last—experience with Detroit’s bussing system.

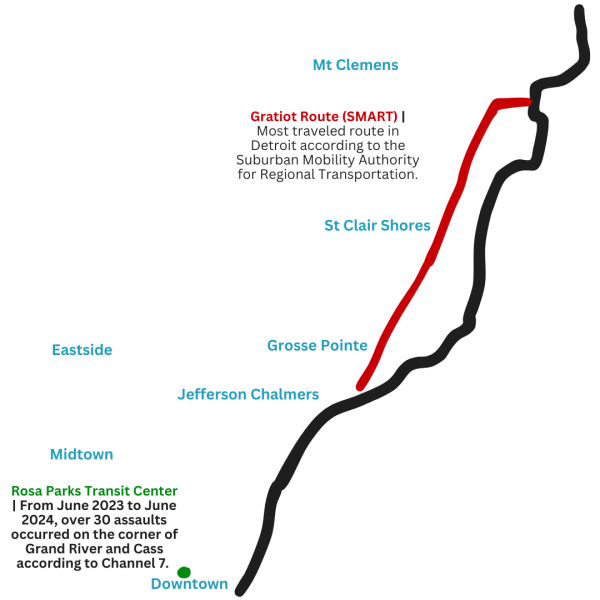

Detroit’s public transit primarily relies on buses operated by the Detroit Department of Transportation and the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation. With 48 different bus routes connecting Detroit to nearby suburbs, including Grosse Pointe, individuals commuting in the metropolitan area tend to frequent DDOT, with over 1 million recurring monthly riders since March 2024, according to the Detroit Department of Transportation.

“Before that happened, I had never taken the bus, and I would never again,” Butcher-Harris said. “For people that have to take the bus every day, they’re seeing stuff like that, and they’re just used to and immune to it now.”

As someone who grew up in the suburbs of Detroit, Butcher-Harris relays that her experience was just a glimpse of the harsh realities faced by Detroiters reliant on public transportation.

“Kids that are with their parents sometimes get exposed to bad influences and it’s not the best experience because sometimes it’s not clean,” Butcher-Harris said. “It’s also very late, and sometimes when it’s cold, you’re just standing out there, and the little waiting places are not big enough for people that want to wait. For accessibility, I think that there are a good amount of bus stops around Detroit, but there could be more because in certain areas, you have to walk a certain amount of miles to find the nearest bus stop.”

Despite acknowledging that the Detroit People Mover, a 2.9-mile elevated rail system, hardly scratches the surface of Detroit’s residential areas, Butcher-Harris believes that it allows some individuals to commute Downtown easily, yet she emphasizes that there is still work to be done.

“People that need to get to work, they can take the People Mover downtown to get to where they need to go,” Butcher-Harris said. “But I think that transportation could be a lot cleaner. I think that you [should] have to get a bus card and before giving someone that have background checks.”

New York City

In October, senior Leilani Feltman traveled to New York City to see a musical and participate in a college tour. During Feltman’s time there, she used public transportation, similar to many people who live in the Big Apple.

With 472 subway stations, 238 local bus routes, 20 Select Bus Service routes and 75 express routes, public transit plays a large role in how people commute around the city. Taxis and buses are widely used, but the subway is the most popular public transportation. According to the MTA, the subway’s daily ridership in 2023 was approximately 3.6 million compared to buses in 2023, which had a daily ridership of 1.4 million. To millions of citizens, the accessibility and inexpensive nature of the subway is a key component to making rides around New York City quick and easy.

“I thought it was really convenient and really inexpensive compared to Uber and taxis,” Feltman said. “And it’s very easy to navigate.”

Even with the easy accessibility, Feltman notes that public transit is not always pristine. She acknowledges that violence has become a major problem on the New York subway, with over 9000 crimes in December 2024 despite a crime rate drop compared to the year prior, according to the New York Police Department.

“With the violence, it is scary because I feel like the subways are a really vulnerable place because once you’re on the train, you’re on that train till the next stop,” Feltman said. “So there is definitely a chance that if violence broke out, it would definitely be alarming.”

According to nye.gov, the rates of crime have decreased with the increase in the number of city police officers. In February 2024, Mayor Adams instructed the NYPD to surge 1000 officers into the subway each day to keep New Yorkers safe, which Feltman believes will benefit the safety of the subways.

“I think that the law enforcement in New York just needs to stay on that,” Feltman said. “And while it’s already been a big problem in the past, they need to help so that it doesn’t become an even bigger issue.”

Chicago

Chatter and Monday morning bustle filled the station as English teacher Kristen Alles boarded the brown line train in the Chicago neighborhood of Lakeview, a part of her daily commute to her job in the Southwest borders of the city. In 2009, Alles first arrived in Chicago for a job teaching at an all-girls Catholic school, and like many Chicagoans, Alles frequently used public transit.

The most popular mode of public transit in Chicago is the elevated or L train. The L is run by the Chicago Transit Authority, which is also in charge of managing the city’s bus system. According to the Civic Federation, in 2023 alone, there were around 274 million CTA riderships.

“You can find a bus or a train no matter where you live,” Alles said. “I think it does a great job of connecting the people in the community.”

The Chicago public transit system is a heavily reliable means of transportation for citizens, including Alles, to get them around the city. According to the CTA’s website, at the start of 2023, the bus service delivered was 92.7%, while the rail service delivered was 80.6%. Having left Chicago 16 years ago, Alles agrees that the reliability of the CTA was the same as when she lived there.

“I don’t think I can remember any moment where I couldn’t catch it or just didn’t,” Alles said. “It was always working.”

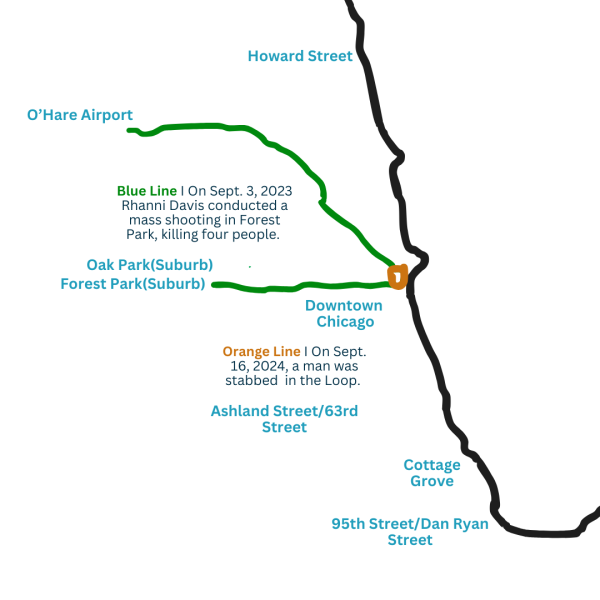

However, one problem that the CTA has faced in recent years is its rising crime rates. Data from the City of Chicago displays that in 2024, the number of batteries committed on CTA property has gone up about 66% since 2023. Though Alles recognizes the risks of traveling the CTA, she understands that it is also a matter of looking out for yourself.

“Once you learn the ways to do it [paying attention to your surroundings] you become alert and aware, and a lot more empowered,” Alles said. “There’s always going to be danger, but I feel like the pros outweigh the cons.”

A city that should not sleep on its safety

I remember the cold March morning when I booked it down the dirt-filled stairs of Times Square–42 St station, weaving through swarms of people in Midtown Manhattan and standing on the subway platform with a growing sense of unease. As I waited for the 1 train to take me uptown for a tour at Barnard College, I could sense the collective tension—eyes darting across the station to ensure they were safe.

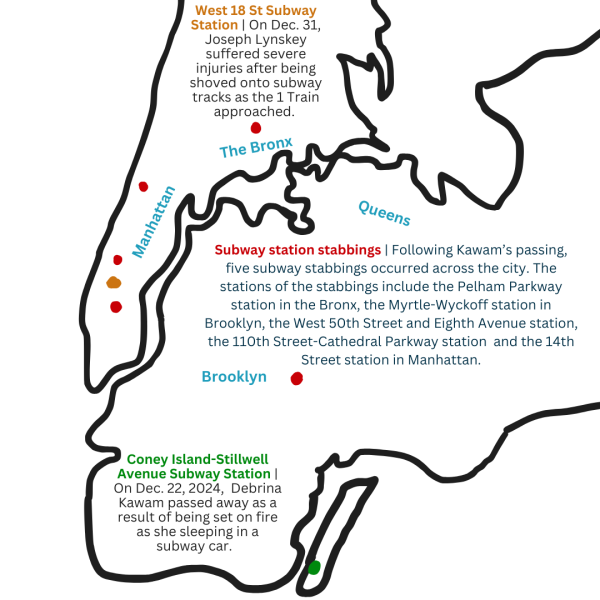

This unease has only grown since the spring. Every week, it seems, another story about subway violence makes the news. A rider shoved onto the tracks. Multiple stabbed in stations across the city. A woman set on fire in a subway car filled with passengers. As of the past few months, it appears that the once-endeared subway system is now on its decline.

In New York, delays and crime in public transportation disproportionately impact low-income riders, who rely on these systems to get to work, school and other necessary locations. Though other cities, including Detroit and Chicago, face transit issues stemming from decades of divestment and high crime, New York’s subways were supposed to be different. They served as a model for the rest of the country—proof that a massive, interconnected city could move millions of people efficiently and safely.

Yet here we are. Each time I travel to New York, I always anticipate a little bit of chaos. However, this emergence of extreme violence over the past few months leaves me truly anxious when I scan my MetroCard. I want to love the subways and be in a place where cars are not necessary, but the city’s inability to reduce subway crime hinders this.

As I prepare to move to New York to attend Barnard College of Columbia University, I can only hope that both cities will reform their public transportation systems. In New York, police should prioritize violence in the subways over individuals hopping the turnstile while also installing platform barriers to enhance safety. But until then, I will be standing behind a pillar on the subway platform, keeping an eye out for myself and others.

Sophomore Mia Melhem | “Detroit should expand the transportation systems to connect to suburbs, as well as the city. Also to improve efficiency and improve the amount of people having access to these systems.”

Junior Silas Wooten | “I think what would be better is having nicer train cars [in New York City] because sometimes they could be very disgusting, so maybe having it cleaned more often would be helpful.”

Teacher Bradley Smith |“It was a very consistent bus schedule in Chicago, which I liked, and so I don’t know about improvements. They’ve done a pretty good job.”